And today we’re going looking through the triangular window…

Not that there was a triangular window in the BBC classic ‘Playschool’ ….

…but when it comes to adoption, negotiating the triangle shaped view is key.

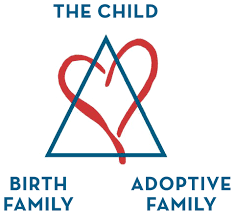

The theory of the Adoption Triangle was introduced early on in the council training. As prospective adoptive parents at the line we are most aware of and keen to establish the line that will connect us to our adoptive child – but what of the other two lines? You don’t get far in the process without it becoming clear that our adopted children do not come to us in a vacuum. Long gone are the days of covering up adoption, hiding it away, re-writing history – so in what way will we carry history – or in our case her-story within our family as a part of our daughter’s life?

Our children have a birth family – and always will. That line on the triangle from child to birth family is not one that is cut when the adoption papers are signed. A birth family is not a mere back story with certain therapeutic properties, some helpful medical information and a neat THE END on the final page. Our child’s birth family are an ongoing reality in our children’s lives and therefore in our lives. Which brings us to the third line of the triangle – our relationship to our child’s birth family.

In our training we were encouraged to enter into this dynamic with compassion and empathy. The focus was on our initial reactions during the matching process when we wade through reports inevitably full of negatives: failures, shortcomings, neglect, cruelty… We were also talked through the benefits of a face to face meeting with birth parents – which in our case is yet to happen – and introduced to the formal / agreed elements that are put in place with your social workers: indirect letter box contact and possibly direct sibling contact – depending on circumstance.

But what I am now (6 months in) starting to consider more deeply is the non-formal, ongoing nature of life in the triangle and what that might look like through the years. And what I am realising is that the answer to that question is largely up to me – at least for a quite a few years to come. How accessible do we make the life story book and more importantly how accessible do we make ourselves to our child on this topic? How much will we talk about birth family and what tone will we strike? Do we put pictures of them up on the wall? How much, if anything do we make of birth family birthdays?

These are just questions at this stage – no answers yet. But perhaps more important than the answers – which will inevitably vary from family to family and through various life stages – are the emotions and motives underlying them all.

Here – as in all therapeutic parenting – I need to be self-aware and self-regulate so that, in due course I can help my little one negotiate these tricky emotions .

So what’s going on with me? Well I am going to be really honest here – and these are not things that I am proud to be typing! Here goes – I feel less secure as my little one’s mum when I receive news that her birth mum is doing well. Which therefore means that I feel ‘better’ when she is not doing well. I hate that I feel that way – but I do. And I think there are various reasons behind that.

Let’s start with guilt. I think I feel less guilty for having the privilege to call this beautiful person my daughter when the circumstances in her birth family match more closely the situation that she was taken out of. It is as if I need ongoing justification for having her, reassurance that I haven’t stolen someone’s child and be required to give her back, reassurance that I am not the bad guy. Because life seems easier when there are good guys and bad guys – particularly when we can cast ourselves as one of the good guys. But that’s not life – that’s a fairy tale version of life and I need to resist buying into it. I need to resist even when people do their best to cast me as the good guy: ‘She’s such a lucky little girl!” – because it is just more messy than that. We are not the happy ending – hey join my house at dinner time and that will becomes clear in a matter of minutes – because the story is still being written and I’m just glad I am in it!

And then there’s fear. Firstly fear that I am less of a mother to my daughter the more potential for mothering her birth mother shows. And linked to that is the fear that with an improvement in birth mum’s circumstances comes an increased likelihood that I will have to share my daughter in the future.

I’m so sorry – I warned you it wasn’t pretty! Please know that I see how ugly that all is. And I deeply believe that none of my children have ever been or will ever be mine to keep. I can do my best to keep them safe, keep them sure of my love, keep them warm and fed, but it is not for me to keep them all to myself.

If I am going to be able to walk my daughter through this, to hold her hand through all this, I need to get some things straight.

I need to know – because she needs to know – that her birth family does not diminish our family. It is because of her birth family that she is who she is and that is just the way we love her to be. To love my little one is not just to tolerate the presence of her birth family in our lives, to pay lip service to it, but to embrace it.

There is not a shadow of a doubt in my mind that my little one is any less my daughter because I didn’t give birth to her. The fact that there is another woman out there who gave birth to her and who loves her does not diminish or challenge that. Indeed, the better parts of me can see that it can only be good for her to be loved by two women and all the more so if I can love that woman too! Afterall, the empathy we were encouraged to have for birth families doesn’t have an expiry date.

Of course the wobbly parts of me (and believe me these are not reserved for adoptive matters, but roam freely all over my mummying) still have some questions. “Just because I am certain that she is no less my daughter, does it follow that I am no less her mother? Or is that up to her? Is she as stuck with me as my other children are?” And the answers? All I can offer as an answer is – we’ll see. Parenting is a high risk occupation – to love that much, in that way is a costly business – but boy is it worth it.

So yes, sometimes life can be a bit triangular and sometimes that can hurt. For example – in the midst of all the fun and celebration of little one’s birthday I hurt for her birth mum, and I hurt that I couldn’t even narrate the day of my daughter’s birth to her, and I hurt that I hadn’t shared in it. And that’s OK – because that’s what love does.

And of course, most of time life isn’t triangular at all – it’s just, well…….life shaped.